Researchers from Los Angeles’s university (UCLA) have developed synthetic T-cells that near-perfectly mimic form and function of the human version.

T-lymphocytes play a key role in the immune system. They are activated when infection enters the body and they flow through the bloodstream to reach the infected areas. Because they must squeeze between small pores, T-cells have the ability to deform to as small as one-quarter of their normal size. They also can grow to almost three times their original size, which helps them fight off the antigens that attack the immune system.

The team of scientists headed by Alireza Moshaverinia, have presented super‐soft functional microparticles that mimic the mechanobiological features of T cells. These particles can penetrate 3D microenvironments, have prolonged blood circulation, and can release various cytokines on demand.

The replication of T-cells in the lab is very difficult

The imitation of T-cells in the lab is very difficult due to their multifunctional nature and the complex structure, and natural T-lymphocytes are difficult to use in research because they only survive a few days after they are extracted from humans. The ability to create the artificial cells could be a key step toward more effective drugs to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases and could lead to a better understanding of human immune cells’ behavior.

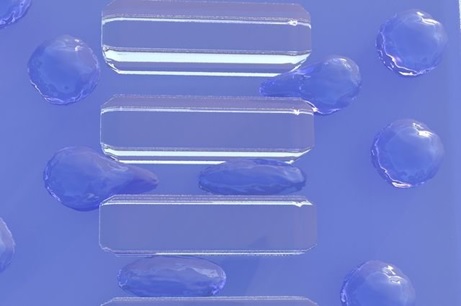

The scientists fabricated T-lymphocytes using a microfluidic system. They combined two different solutions — mineral oil and an alginate biopolymer, a gum-like substance made from polysaccharides and water. When the two fluids combine, they create microparticles of alginate, which replicate the form and structure of natural T-cells.

Until recently, bioengineers hadn’t been able to create synthetic copies of human T-cells. But the UCLA researchers were able to imitate their shape, size and flexibility, which enable the synthetic version to perform its basic functions of targeting and homing in on infections.

The biological properties which give them the ability to be activated to fight infection or regulate inflammation was enabled by using a chemical process called bioconjugation to link the synthetic T-cells with particles that activate natural T-cells (CD4 signalers).

According to the research team other scientists could use the same process to create various types of artificial cells. In the future, the approach could help scientists develop a database of a wide range of synthetic cells that mimic human cells!